Riding up the Quito River, trees claw their way to the edges of the riverbanks, forming an impenetrable forest wall lining the water.

Then, suddenly, the world opens.

The trees that walled us in have jumped back more than half a kilometer, leaving a barren wasteland. The river, which had until then gently curved back and forth, is now a nearly straight line.

Then, the first dragon appears.

SEE ALSO: Digging Into a Toxic Trade: Illegal Mining in Amazon Tri-Border Regions

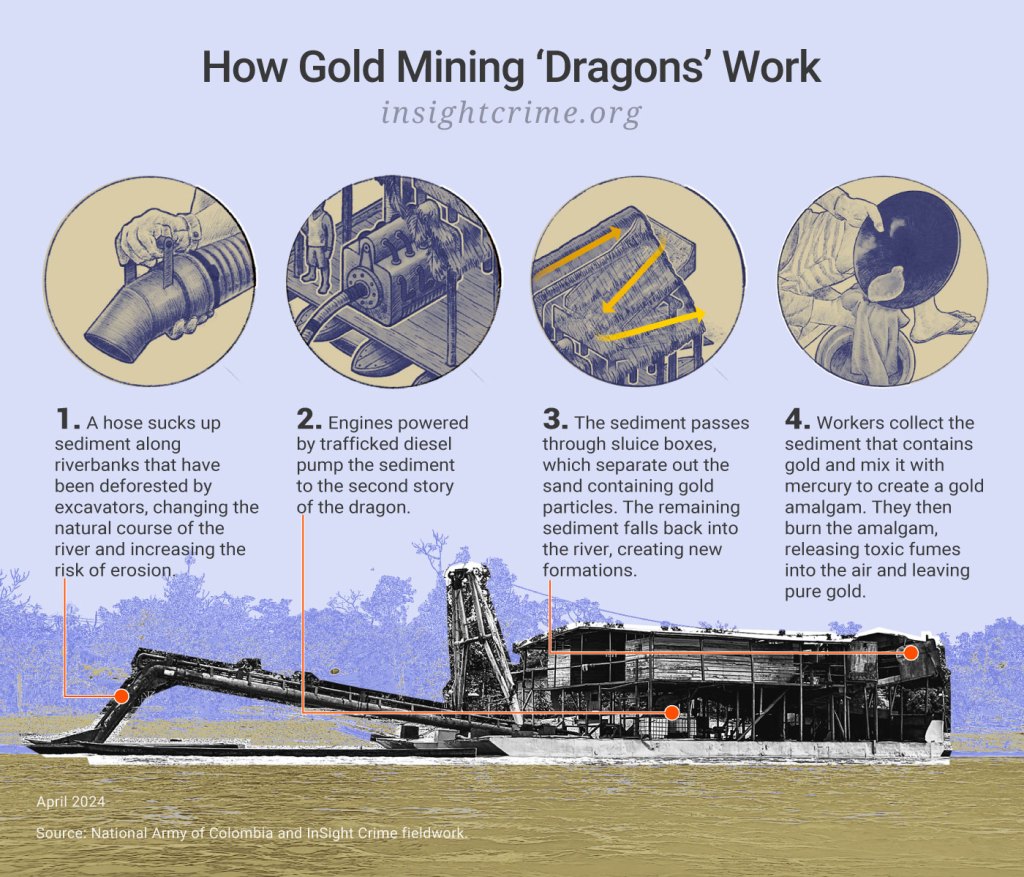

Dragons are boatlike machines, which look like a mix between an excavator, a raft, and a shanty house perched high on stilts. And like the dragons of lore, these also stockpile gold.

Miners use these large dredges to extract gold, biting chunks out of the forest and tossing the mercury and arsenic-poisoned leftovers to the side.

Dragons are boatlike machines, which look like a mix between an excavator, a raft, and a shanty house perched high on stilts. And like the dragons of lore, these also stockpile gold.

The process of mining gold has had devastating environmental impacts in the department of Chocó, on Colombia’s Pacific coast. Record-high international gold prices over the last five years have spurred a rush in Chocó’s southern mining regions. Behind the large-scale illegal gold mining are criminal groups who fight each other for control of the region: the paramilitary successor group known as the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia – AGC) and the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN) guerrillas.

Unlike other illegal economies, illegal gold mining happens in plain sight. It takes less than an hour by boat from the city of Quibdó, the capital of Chocó, to reach these gold-mining monsters.

A Dragon’s Hoard of Gold

It’s 7:00 a.m. and pouring. But despite the hour and the storm, Quibdó’s river port — which is little more than a stone staircase descending into the Atrato River — is full of vendors and barefoot boat captains in navy ponchos shouting offers for their services.

One such skipper is our guide, Tomás.*

He helps us onto his boat, placing cut-down plastic lawn chairs in the hull so our weight is evenly distributed. He revs the engine, and we push off from the concrete riverbank.

Our destination is the town of Paimadó in Río Quito, a municipality neighboring Quibdó, which has suffered the effects of illegal gold mining for over a decade.

“Don’t take any pictures now on the way to Paimadó,” Tomás warns. “If you’re going to take out your phones, it’s better to do it on the way back.”

The area is controlled by the AGC, which, according to military sources, funds and owns some dragons operating on the Quito River. Other dredges are allegedly owned by shady investors who may never have set foot in Chocó.

The AGC has imposed a 6:00 p.m. curfew on the river, limiting local commerce. Miners, however, are still allowed to travel at night, said Tomás, “because they’re producing for [the AGC], and we aren’t.”

The group also profits from mining operations it doesn’t own. All miners have to pay a percentage of the gold they mine as an extortion fee.

We count at least 10 dragons between the small town of San Isidro and Paimadó. But military sources who spoke on condition of anonymity estimate there are between 40 and 70 of these dredges across the department.

“The dredges are a serious problem. The armed groups come along with them, and we have to work for them. Because if someone says no, well…”

tomás

Each dragon costs around 1.5 million Colombian pesos, or about $400,000, to build, according to military sources. But the profits far outweigh the costs. Each dredge can extract around 1 kilogram of gold per week, which is nearly worth $77,000 on the international market. Annual revenues for each dragon could amount to more than $4 million per year.

Colombians and foreigners alike do the manual labor on the dredges. Some Colombian workers travel from the nearby departments of Antioquia, Caldas, and Risaralda, though most come from local communities in Chocó.

But these employment opportunities come at a cost.

“The dredges are a serious problem. The armed groups come along with them, and we have to work for them,” Tomás says, adding, “Because if someone says no, well…”

A Ravaged Ecosystem

The shores around the dragons are pocked with unnatural coves and piles of gray sediment. Every so often, we feel a jarring clunk as the hull of the boat runs into a felled log or branch hidden beneath the river’s surface. Tomás, in well-practiced response, cuts the engine’s power and lifts the propeller out of the water in a matter of milliseconds to keep the wood from causing damage.

The dragons suck up sediment from the riverbed using a hose, pumping it over a carpet-lined sluice, which traps gold-containing sediment using mercury. A chemical reaction causes the mercury and gold to form a mixture called an amalgam. Workers on the dragon take the amalgam and heat it so that the mercury evaporates, leaving the gold behind.

The process emits toxic gases into the air. The remaining substances are tossed into the river, contaminating it and the fish that feed local communities.

“Nobody does anything for us … We’re dying from mercury, from malaria, from dengue. We’re screwed.”

Tomás

“Nobody does anything for us … We’re dying from mercury, from malaria, from dengue. We’re screwed,” lamented Tomás when we first spoke days before our journey.

Exposure to mercury, even in small amounts, can cause serious health issues and even death. In Chocó, mercury levels are not regularly monitored. The only investigation from the last six years shows dangerously high levels in rural populations. The 2018 National Water Study estimated that there were 183 metric tons of mercury dumped into Colombia’s waterways. Between 2017 and 2022, 37.9 tons of gold were officially recorded in Chocó, according to a report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), though with illegally mined gold, the total is likely much higher. For each gram of gold produced, between 7 to 30 grams of mercury may be used. That means nearly 265 tons of mercury were used only for the gold reported in the last five years.

The mercury issue has overshadowed other serious problems caused by illegal mining, like soil destruction, according to a representative from the Beteguma Foundation, an environmental nonprofit.

“They have basically rerouted this river,” the source said, speaking anonymously due to security concerns.

The dragons have made the Quito River their home for over a decade. As gold deposits dry up in the south, they have moved further downstream, dredging more and more of the river. This causes increased flooding and erosion upstream, as water moves more rapidly through the dredged areas. As the river erodes its banks, the loose sediment can clog streams, kill fish, and destabilize ports and bridges.

Towns along the river are suffering from these effects. Paimadó, for example, built a retention wall to prevent erosion. But with no rock bed to build into, the water has continued to erode the town’s banks, coming dangerously close to homes and businesses.

Tomás navigates the backwaters expertly, and as we travel further south, the river banks and dragon-made islands that dot the landscape eventually show some signs of life with small bushes and saplings. But, the river is a complex, interconnected ecosystem, and recovery could take years. That is unlikely if operations continue damaging other parts of the river, said the Beteguma Foundation representative.

Artisanal Mining: A Cultural Responsibility

In between groups of dragons, we turn a river bend and see a group of young men in chest-deep water shoveling sediment into small wooden canoes. Shortly after, a man and a woman have set up a small sluice on a gray beach.

These are barequeros, known legally as subsistence miners, but who prefer to call themselves artisanal miners.

Chocó has a large Afro-Colombian population — over 78% of the department’s population as of 2018 — most of whom are descended from enslaved people forced to mine for gold. After slavery was abolished, artisanal mining became a cultural cornerstone of the Black communities that stayed in the department.

“Mining is a cultural, emotional, spiritual, and ancestral activity,” said a representative of the Atabaque Foundation, an NGO in southern Chocó that helps barequeros formalize their activities.

“Mining is a cultural, emotional, spiritual, and ancestral activity,” said a representative of an NGO in southern Chocó that helps barequeros formalize their activities.

Barequeros have to register each year with the nearest mayor’s office and must have a working email and phone number. However, most miners live and work in rural areas that may be up to a day’s travel away from the mayor’s office, and they fail to register because they cannot afford to lose a day or two of work.

As a result, many artisanal miners and local mining collectives operate without formal documentation, which can be near-impossible to obtain. During military operations against illegal mining, authorities often target both artisanal miners working without permits, as well as mining operations run by organized crime. The distinction between the two is further complicated by the fact that many barequeros are forced to pay a tax to local criminal groups.

Mining cooperatives in communal land also struggle to formalize. A Quibdó mining association told InSight Crime that they started applying for a mining title in 2009 but have yet to be approved, as the requirements and costs change every few months.

Everybody’s Problem and Nobody’s Problem

As we arrive in Paimadó, a man jumps out of his boat and walks past us to a gas station, bidding us good morning in an accent that is not from this area. Once we are safely out of earshot, Tomás tells us in hushed tones that he’s a paraco, local slang for a member of the AGC.

The alleged paraco and his companions filled up two boats’ worth of fuel containers with diesel. This fuel could be bound for one of the dragons or excavators we passed on the way to Paimadó, which is deep in AGC territory.

Until 2016, the area was controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC). After the guerrilla group signed a peace treaty with the Colombian government and disarmed, other armed groups began to move in. But it was not until after the COVID-19 pandemic that clashes between the AGC and ELN really started to escalate.

SEE ALSO: From Total to Partial Peace: Colombia’s Talks With Crime Groups Fragment

“It’s been three years of recurring emergencies that the government knows about. The state knows, community leaders know, everybody knows, because we report them. But those who have the responsibility to respond to the emergencies don’t do it,” a social leader in southern Chocó told InSight Crime.

The civilian population suffers these violent clashes the most, weathering mass displacements, confinements, land mines, and threats.

Neither officials nor other agencies have had much success at dismantling mining operations. The state’s primary response to the illegal mining taking place along the Quito River has been to launch military operations. Days before we visited Paimadó, 350 men were deployed in one such operation on the Quito and Atrato rivers. As usual, officials seized some machinery, but made no arrests.

In theory, the military is responsible for interdiction, Chocó’s environmental regulations agency (Codechocó) for imposing administrative sanctions, and the Attorney General’s Office for prosecuting those responsible. But in reality, none of this happens.

A representative of the Attorney General’s Office told us that cooperation between the three groups is severely lacking, a claim that was confirmed by a representative of Codechocó.

A representative of an environmental NGO in Quibdó told InSight Crime that corrupt officials warn the miners when a military operation is planned, so the workers can escape ahead of time. He scoffed at the seized dragons, which are often merely left on the riverbank to rust. “So the military shows up and does their thing, and people say the dragons have been destroyed because you can see the flames and the explosion. But eventually, the dredges return and begin working again.”

*Name has been changed to protect identity.

Credit: Source link