By Alden Wicker,Features correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPre-owned clothing is a surging market with a cool reputation. Yet the economics don’t make sense, and most companies are struggling.

In the past decade, buying used fashion has become normalised and even glamorised, with celebrities getting in on the action through swaps and sales of their pre-owned designer clothing. Shoppers are paying TikTok stylists hundreds of dollars for “bundles” of thrifted clothing, and the fashion sponsor of the popular British reality show Love Island switched from a fast-fashion brand to eBay.

Sixty-seven percent of millennials in the UK shop second-hand, and according to a report commissioned by ThredUp, the online second-hand fashion retailer, two in five items in Gen Z’s closet are pre-owned. Every year since 2017, ThredUp has put out this report underlining the breakneck growth of the market. Its latest version of the report noted that by 2027, the value of the fashion resale market would double, to $3.5bn (£2.76bn).

As large as the opportunity is, however, there’s a big problem. From local thrift shops to enormous online second-hand retailers, it’s hard to find pre-owned clothing businesses that actually turn a profit.

Supply > demand

Online retailers have been packing up and shipping out second-hand clothes for years, focusing on growth over the bottom line, taking on large capital investments and, in some cases, going public. Despite this commitment, profits aren’t rolling in – even for the biggest players in the space.

Courtesy of ThredUp

Courtesy of ThredUpFor instance, neither the American companies ThredUp nor its luxury cousin The RealReal are profitable, disappointing investors and dragging share prices below their IPOs. In 2022, fewer than two years after going public, the American peer-to-peer resale site Poshmark was acquired by a Korean tech company for $1.2bn (£950m), one-sixth of its IPO valuation. While the service is still available to American shoppers and sellers, the company no longer operates in the UK market.

The Lithuanian peer-to-peer fashion resale start-up Vinted has taken over in the UK, posting a pre-tax loss of €47.1m ($51m; £40.3m) in 2022. The British second-hand marketplace Depop posted a loss of £59m ($69m) in 2023. The bright spot is Vestiaire, which focuses on luxury resale. If its optimistic forecast is to be believed, it might be profitable by the end of the year.

This struggle affects every size, type and location of resellers. For-profit second-hand clothing sorters in the UK have been going out of business, citing high labour costs and the degrading quality of the clothing they receive. In New York City, Brooklyn residents bemoan standing in line for an hour to consign clothes at the famous store Beacon’s Closet, and getting paid just $18 (£14.20) for a full bag of old designer clothes. As early as 2016, market resellers in Ghana – one of the largest recipients of second-hand fashion from Europe – were also complaining about declining quality and profits, and it has only gotten worse since then.

The problem is one of economics. With the rise of ultra-fast, ultra-cheap fashion brands, the volume of clothing produced and shipped globally continues to explode, and consumers are offloading more of it after just a few wears.

“There’s an oversupply of clothes,” says Liz Ricketts, co-founder and executive director of The Or Foundation, a non-profit that researches Ghana’s Kantamanto market, one of the world’s largest clothing exchanges. “And it’s lowering the perceived value, and the real value, of everything.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHidden costs

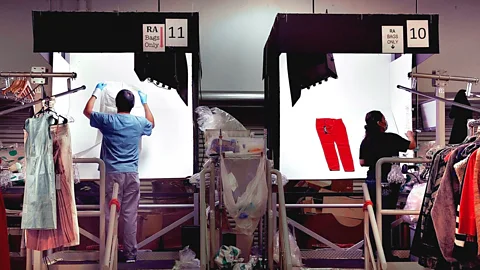

Processing second-hand products is labour-intensive – and it’s costly for businesses. “We treat waste as if it is a free resource. Sure, you might give it away for free, but it takes a tremendous amount of effort and labour and skill to try to re-commodify that thing that you gave away,” says Ricketts. “Reuse is based on the quality and the condition of the individual item, which means that it requires a human touch and a human eye to assess that.”

Second-hand clothing companies have realised the difficult economics of processing old clothes for resale. To shore up business, some are changing their models for acquiring pre-owned clothing. ThredUp is now charging consumers and brands alike to process their old clothing, whereas sending along a “Clean Out Kit” was previously free.

“You’re doing effectively reverse, single-SKU fulfilment, which is incredibly difficult, incredibly expensive and incredibly inefficient,” says Dylan Carden, a US-based research analyst at the investment firm William Blair.

Rising costs can mean rising price, a jarring realisation for consumers who come to the market expecting deals and steals. In some cases, labour costs can push the price of second-hand clothing over the price of new products of similar quality. A recent investigation by The Telegraph called thrift shopping in the UK a “right rip-off”, citing the example of a used Primark sweater that was priced higher than a new one.

Thomas Bauwens, an economist and assistant professor in collective action and sustainability at Rotterdam School of Management, believes that we would have to completely rethink what we consider a “good” or “healthy” economy for second-hand retail to succeed. In a 2021 article in the Journal of Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Bauwens argued that, in a growth-based economy, companies trying to implement sustainable practices such as take-back, repair, resale and recycling are “quickly outpriced and driven out of the market by cheaper, non-circular competitors”.

A climate imperative

Some experts believe the key to making the pre-owned clothing market work is by not only treating it as a for-profit business – but also as an environmental imperative.

Getty Images

Getty Images“The resale [industry] as we know it today – not the thrift shopping from when we grew up – is in its infancy,” says Rachel Kibbe, CEO of the trade group American Circular Textiles. She believes the second-hand clothing market should receive funding for capital-intensive sorting and recycling infrastructure to reduce labour costs, the same way other climate-focused initiatives are subsidised.

William Blair’s Carden thinks ThredUp and its ilk could benefit from government regulation that requires companies use certain technology to reduce labour costs. For instance, scannable tags on garments can pull up information and photos on each item instantly, which would slash the amount of manual labour required to sort clothing.

These kinds of changes are not only eco-friendly, but may also lead some resellers to profitability as they introduce efficiencies and scale up business models with new, state-of-the-art fulfilment centres and technology.

Reducing the oversupply of clothing could also be key. “I don’t see a world where second-hand and upcycled and recycled products are going to be competitive if we don’t reduce the production of new clothes,” says Ricketts. Her organisation is calling for a government policy that would include a reduction of the production of new clothes by 40%.

Whether the second-hand clothing market is a bubble ready to burst, or an industry with untapped potential, experts agree the current situation is untenable. “We need infrastructure, we need labour, we need capital,” says Kibbe. “Because how else are we going to solve this thing called the climate crisis?”

Credit: Source link