The Sailing Vessel Rosa Lux was finally at her summer home, a mooring at the Miramar Yacht Club in Sheepshead Bay. Four members of the Communal Luxury Yacht Club initially wanted to set sail at 9 a.m. on a Sunday in early June, but because of the boat’s broken motor, we were dependent on the wind, which would be a safer bet around noon. We met near the club’s dock, where de facto captain Gavin Schalliol spread out a nautical map on a picnic table and charted our plans for the day. We would leave, go out to Coney Island, and head back by 3 p.m. to avoid low tide. We weren’t chatting long before an incredibly chipper woman came by to offer us Italian cookies. “They melt in your mouth!” she insisted; she didn’t lie. Cookies consumed, we took a small motorboat to the mooring—like a valet service for marinas—and then finally climbed aboard.

The boat’s maiden summer voyage started with a mistake. “Surprise!” Schalliol yelled, as he realized the boat came off the mooring unexpectedly quickly. We moved slowly at first, navigating out of the small Sheepshead Bay channel into the Rockaway Inlet. We laughed at the names of other boats we passed—one just called “Sex Drive,” another called “Chaos”—and took turns tacking and jibing, a process that required coordinated pulling and releasing of ropes on opposite sides of the cockpit. It became clear, quickly, that while one person technically could single-hand a boat this size, it was much easier as a collective. Schalliol had the lively and patient register of a kindergarten teacher as he quizzed other members of the collective on right-of-way water rules.

Fifty years old, this ship is not in prime racing condition, but her sailors aren’t exactly aiming for speed. For members of the loose sailing collective known as the Communal Luxury Yacht Club, the sloop represents a chance to practice autonomy. “The availability of cheap fiberglass boats is an opportunity for people to experiment and learn skills together,” Schalliol said recently. To him and other members of the club, the boat is a vessel for freedom.

There is a rich tradition of anarchists and artists taking to America’s waterways in search of a life outside capitalism, but Communal Luxury is more interested in making boating as a pastime accessible. While more adventurous boaters in New York have taken up full-time residence in its polluted creeks and waterways, the collective seeks to expand access to sailing while keeping the activity, at its core, a hobby and a luxury.

“‘Communal Luxury’ is a little bit tongue in cheek,” Ben Leo, one of the group’s founding members, said. “But it really is a communal luxury item. A huge part of it is community-building around leisure. We’re not saving any lives here. We’re not really making any grand statements. We’re coming together and we’re enjoying things that are outside of necessities in life.”

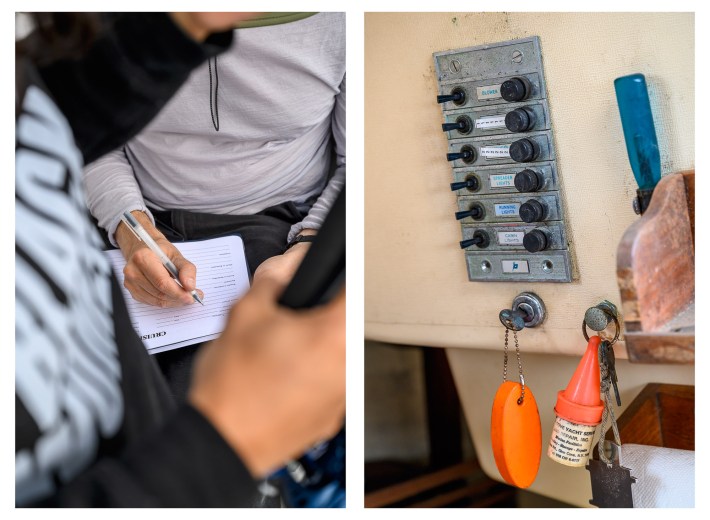

Schalliol underscored an inherent collectivism in sailing: “Boats are these self-contained living quarters where you can provision for it, you can have your own water and electrical systems on board.” And if they pick up some life skills along the way to make their lives off the boat more independent, that’s a nice added bonus. “Sometimes I think, ‘Oh, I really should learn how to fabricate stuff with wood,’ or ‘I really should learn how to fix up an electrical system,'” Schalliol said. “And that all sounds really boring. But if you do it on a boat, suddenly, it’s fun.”

The Rosa Lux (get it?) is a Pearson 30: a sailboat with a motor and thus “the ability to ‘go both ways,'” as its manufacturer boasted in a 1975 brochure. It’s a 30-foot craft with a deceptively large seven-foot cockpit, a “racer-cruiser” built for both speed and leisure. Pearson Yacht’s head designer William Shaw used it as his personal boat for years. Before Pearson ceased its production in 1981, the boat could easily fetch $35,000, especially with the addition of LectraSan toilets and custom sound systems. But like a copy of Fleetwood Mac’s “Rumours,” the boat was so heavily manufactured in the ’70s that it’s surprisingly affordable today. “The Pierson 30 is a boat that some people sail across oceans, and [a former member] got it for $400” from a charity write-off boat auction site called Boat Angel, Schalliol recalled.

A few more things separate the collective’s members from a typical yachting group. While the average age of boat ownership dipped a bit during the pandemic, likely owing to a desire to escape to the great outdoors, it still hovers well above 40. Even on the low end, boats can run their owners up at least $5,000 a year, and that’s after the upfront cost of buying a damn boat. By contrast, Communal Luxury sailors are young, did not necessarily grow up learning to sail, and were not incredibly wealthy.

Getting involved with the Communal Luxury Yacht Club is as easy as messaging the collective on Instagram. To that end, there are about 90 casual members who belong to the group’s general Signal chat. Those who want to take their membership out of the group chat and onto the high seas, however, must commit to annual maintenance fees that run around $200 apiece, and contribute their time and labor to repairing the boat. New members are also required to either have prior sailing experience or take a basic sailing class—the collective recommends TASCA, which offers lessons starting at $350 on a seasonal basis.

Still, for members who want to practice sailing, maintaining the Rosa Lux is a bargain. “Sailing, especially if you’re talking about yachts, has such an implication of being super rich, and a lot of that is reality,” collective member Loris D’Emic said. “It’s very expensive. We’re doing this in part to try to bring [costs] down a little bit and make it more accessible for people.”

A core team of five acts as a steering committee (or should it be a tacking committee—sorry, sorry), approving new members who want to set sail. Still, curious sailors shouldn’t be deterred by the approval process. “People are invited to come to work days,” Lori Rodriguez, a core member, told me. “We do try to meet regularly, and we are responsible for the costs of the boat, but we also don’t want there to be really high barriers to entry.”

Despite its name, the Communal Luxury Yacht Club got its start firmly on dry land. The initiative began in 2019 as the Ridgewood Yacht Club, as an informal meeting at Woodbine, a community hub in Queens. At the time, the collective was closer to a reading group. Its members pored over nautical charts and practiced knot-tying while they discussed books like “The Many-Headed Hydra,” a “history of below” of the “Atlantic proletariat” who brought class consciousness to the ocean from the 1600s to the 1800s. The impetus to take the group to the sea came from a former member, Duncan Ranslem. “Duncan had this vision he imparted on a lot of other people,” Schalliol explained. “These old fiberglass boats from the ’70s and ’80s are unloved because the generation that learned how to sail them is getting on in years. But they’re also completely indestructible.”

The early days of the Rosa Lux weren’t exactly smooth sailing. While purchasing the boat was surprisingly easy, there was still the issue of getting it to Brooklyn from its origin port in Mount Sinai, a tiny hamlet on Long Island. “It was an odyssey getting it all the way down to Sheepshead Bay,” Schalliol said. “We had to bring it all the way around Long Island Sound through the East River. We had planned to motor most of the way because it was a long way, but then halfway through, the motor broke down.” They ended up docking at City Island for a few months while they regrouped, but for Schalliol, the experience only strengthened the self-reliant nature of the project. “I just thought that was really cool that we could just improvise when things messed up,” he said. “Systems were relatively simple, such that we could understand them and we could kind of try and fix them ourselves.”

The group initially grew organically through word of mouth. “At first, I thought it was probably a bunch of bullshit,” Rodriguez, an early member, said. “But I showed up at City Island and saw the boat, and came for a few work days.” Rodriguez, like many of the group’s members, had no prior sailing experience, but was eager to bring whatever relevant knowledge she had to the boat. “I do have a background as a bicycle mechanic and have recently gotten into motorcycles. I like doing this DIY stuff,” she said.

On a Sunday in late May, I joined the core members in Arverne, Queens, where they keep the boat on dry land every other year. We met at Seaway Marina, which the group referred to as the “DIY marina.” “A lot of people go to DiMeglio’s [Marina], which is a little bit closer, but you can’t do a bunch of stuff,” Schalliol explained. “If you want to do your own repairs, go here.” The group had recently painted and sanded the boat; this work day would be the last chance for any final repairs before it entered the water for the summer season.

Men on nearby boats, suspended 50 feet in the air to repair their masts, discussed day trips to Connecticut. Meanwhile, the collective ran through a list of maintenance work: Clean the bilge and test out its pump, and replace a corroded propeller nut anode, a small circular piece of metal that acts as “the boat’s liver,” as Nathan Hewitt, another core member, put it, catching debris and buildup from the ocean before it reaches key equipment. The team split up into pairs—Schaillol led a group working on the bilge pump, while I observed Hewitt’s work on the anode. The labor was fairly physical, especially as the Memorial Day weekend sun beat down, but it didn’t necessarily require specialized skills; Hewitt tried to loosen the corroded anode himself, before eventually taking to it with a hammer and bludgeoning it until it fell off the ship’s propeller. In a few weeks, their winter marina, Seaway, would carry Rosa Lux from her dry winter home by crane into the water, a service covered in Seaway’s $1,300 annual storage fee.

To Communal Luxury Yacht Club members, the Rosa Lux is a way to build the skills necessary for self-reliance. They see self-sufficiency through laboring on the boat as a way to reestablish meaning in a world designed to separate us from the work of maintaining our dwellings. “[Sailing] is a good way to start practicing these skills that can help you live more independent lives, and reduce the alienation from all of the things around you that you don’t understand,” Schalliol said.

On a boat, “the stakes are lower” to try new things, he added. “You’re working with 12-volt DC, which will not even really hurt you, unlike utility AC power [which runs in apartments and homes], which will kill you.” Recently, one member with search-and-rescue climbing experience helped them repair a particularly hard to reach spot at the top of the ship’s mast. But their reliance on their own knowledge and labor has its limits. That motor that broke down on their trip from Long Island in 2019? It’s still kicked. Rodriguez has tried to repair it based on her knowledge of motorcycle engines, but for now, the group has found that its issues are beyond their realm of expertise. Over all else, in our conversations, Schalliol wanted to emphasize one thing: “If anybody out there knows anything about Palmer P60 engines, please get in touch.”

It struck me that, with a little sweat equity, it was cheaper to own a boat annually than to rent an apartment monthly in New York. It also struck me, standing in the cockpit, that this was indeed a small craft. For the next week, I eyed ferries and cargo ships with suspicion, envisioning a watery grave every time they left a particularly large wake.

But those fears faded by June, when we finally got out on the water. Half an hour into our sail, I thought back to something Rodriguez said in an earlier conversation: “It is just so fun and so beautiful to be out on the water; it’s really an indescribable feeling.” Wind in my hair, I was just beginning to feel what Herman Melville called the “howling infinite” of the ocean when a flash of New York City came whizzing by: the loud siren of an FDNY boat, which we’d later determine from VHF radio broadcasts came to rescue a capsized catamaran. There were other reminders of the city on the water as we went on—a garbage patch filled with Sour Patch Kids wrappers and pretzel bags, sewage treatment plants surrounded by eager birds—but overall, they felt like outliers in the vastness of the sea.

I didn’t necessarily doubt Leo when he said, “It is pretty much simple as you can get out there,” but I was still shocked by the lack of regulation on the open water. Aside from random updates from the distress safety channel—the Fire Department needed glow sticks, someone had come to save the overturned boat—interactions with the New York City government were surprisingly absent from our time at sea. Though the NYC Parks Department is technically responsible for moorings around the city, most are effectively administered by privately owned clubs like Miramar. In general, the group’s experience with the City government has been minimal, save for one trip where Schalliol called VHR Channel 13 to ask the transportation department to open an MTA bridge. “It’s not like you have to be a super large container ship,” he added, still sounding incredulous as he recounted the interaction. “You have a little conversation with them, and then when the time’s right, they’ll open it for you, even though you’re just a little sailboat.”

Sailing New York’s waterways by wind alone required constant, in-the-moment maintenance: tacking to move us out to the sea without a motor, adjusting the ship’s jib when it became too cumbersome to maneuver, and keeping an eye out for unexpected power boats. There was plenty of the improvisation that Schalliol had mentioned earlier—the boat’s anchor fell behind the ship when we lowered it near Coney Island, forcing us to move the boat slightly to get it into a better position. But all of this navigating and learning as we went felt genuinely fun and liberating out on the water. We weren’t collaborating for the sake of it; we were collaborating around the common goal of a successful sail.

When we got back to shore, we met again at the same picnic table where Schalliol had first spread out the map to regroup after the day. It wasn’t long, though, before we were again interrupted by yet another kind stranger bearing food. This time, it was a feast of burgers, hot dogs, and knishes.

We took our various meats (it didn’t seem like we had a choice), and resumed discussing our day, when another group of Grill Guys interrupted, this time to ask if we wanted any Beyond Meat patties. The group insisted they were a) plenty satisfied with the food they already had and b) not vegan, though they could understand the assumption, but the Grill Guys threw a few meatless burgers on the grill anyway. This marina encounter underscored what so much of the group had said throughout our day at sea: Sailing was about community, whether or not your boat was named after a Marxist revolutionary.

Credit: Source link