PARIS — In Olivier Rousteing’s office perched on the sixth floor of Balmain’s Paris headquarters, stark white walls and black marble surfaces are coated with perfume bottles, bags, and blown-up campaign imagery. Order rubs shoulders with accumulation in the Balmain style, which Rousteing continues to champion as the house’s creative director since 2011: a silhouette that marries powerful shoulders to body-hugging curves and opulent details, projecting womanly glamour and galactic flamboyance.

Raised in the bourgeois city of Bordeaux, the designer now reinterprets the codes of French glamour for a cosmopolitan, radiant woman who knows neither taboos nor borders.

“Heritage, modernity, and inclusivity are the elements that have fuelled my longevity in the house and sum up my career at Balmain,” Rousteing says.

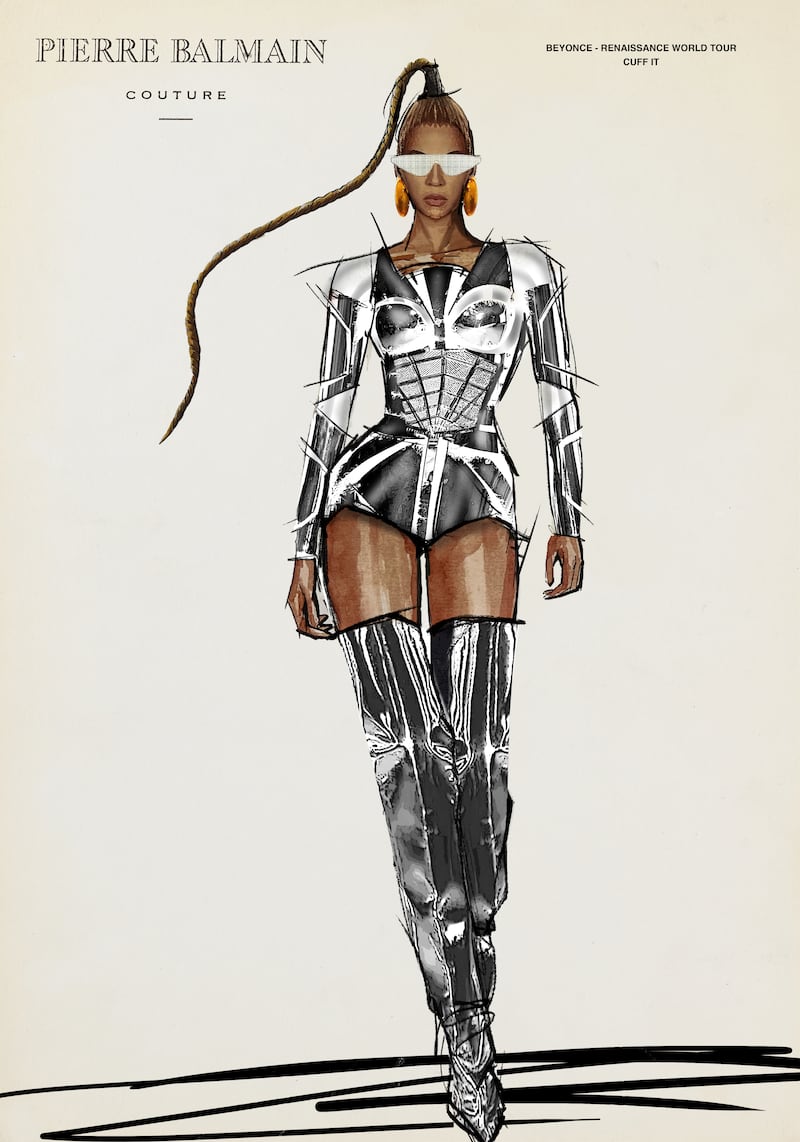

From partnerships with Kim Kardashian and her family to Beyoncé, for whom he has designed costumes for music videos and tours, Rousteing has renewed Balmain’s historic ties to celebrity while taking them to new, global heights. Those partnerships have electrified the designer’s Instagram account — which now counts 10 million followers — as well as powering exponential growth for Mayhoola-owned Balmain, where sales have increased more than ten-fold during his tenure.

In an exclusive interview with BoF, the designer talks about his vision, his longevity, the strength of his doubts, his relationship to social media fame, and the aftermath of a hijacked shipment just days before Paris Fashion Week.

You joined Balmain in 2009, and have been creative director since 2011. How do you account for this kind of longevity in a fashion world dominated by short-term bets?

I have been in these walls for 14 years. I started as the right-hand man [of Christophe Decarnin] in 2009. Being one of the players without being in control allowed me to immerse myself in the DNA of the house.

Since I took over, we’ve structured the project around a few key points: heritage through know-how and couture craftsmanship, modernity, inclusivity, contemporary diversity. The dichotomy between past and present has been at the heart of Balmain’s rebirth. I realised that contradiction would be the force that would define the future of Balmain.

It wasn’t just a dream. The turnover increased from €20 million to €300 million ($322 million). The company has grown from around 40 employees to more than 600.

I owe my success to the fact of having believed in a very precise vision and making it evolve, without having tried to be someone else. A lot of people criticise me because I’m not into pleasing everyone. But my style is precise, even if some find it ostentatious. I’m not trying to convince them.

How do you continue to keep up the excitement, your enthusiasm from season to season? What is the foundation you build your collection on?

I built it on my own flaws: I doubt myself all the time. I live with a dissatisfaction deep inside me that pushes me to go beyond myself, as well as this confidence that allows me to take risks every day.

I dedicate my life to this house. [In the story of Balmain] I can’t tell you if my tenure will be a gigantic chapter, or its own book, as I would hope. But I can say that I was the child of Balmain, and now Balmain is the child I am raising. It’s a special relationship in terms of emotion: all that Balmain gave me, I feel I owe back to it.

How has this relationship evolved?

Continuing here is something I had to do for myself as much as it was about loyalty: I had to prove to people that I wasn’t just a flash in the pan.

What matters most now is embodying the house with very strong codes, with a style that doesn’t succumb to trends. I believe the prestige of a house depends on staying true to itself. I played with the house codes until those codes became mine. Embodying a house means imposing a style, then your own: this is what makes your longevity.

How would you define your style?

Flamboyant, Parisian. The latter more so than ever since my 10th anniversary show, when the style evolved towards more sophistication, more heritage. I don’t want people to think Balmain has existed since 2011 instead of 1945.

Being anchored in pop culture can confine you to a given moment, especially with social media. But I have only been the translator of a style that already existed, using my own language. I was taken for a rebel; I was only a witness to my time.

What does Paris represent, for you?

Paris is the city of lights. It is the international capital. The one who always shines. Paris is Versailles, it’s Place de la Concorde, it’s Centre Pompidou.

The question of identity is at the heart of your story — both as one of few Black designers to have led a major fashion house, and as a child of adoption. How does identity continue still play a role in your career?

When you don’t know where you come from — I don’t know my biological father or mother — you must anchor yourself in something. You must fight to assert your identity, to know where you want to go.

My heritage now is being a Frenchman of African origin — one who has been fighting for twelve years to make a new France shine, beyond Balmain.

To shine — how does this notion of radiance, or brilliance feed into your work?

I dream of a world where we protect ourselves with light. I think of my dresses as shining armour. Being against all forms of violence, of course I’m talking about self-protection. We live in a very hostile world.

There are designers who evoke protection with large, black clothes, very thick things. If I have only one regret, it is having the feeling of being misunderstood, it is seeing that my work has been interpreted as expressing a form of superficiality. Really it has always been linked to the struggles of women who wanted to be themselves.

“There are designers who evoke protection with large, black clothes, very thick things…I dream of a world where we protect ourselves with light.”

“When I was little, I only had one fear: returning to the orphanage, because I was afraid of not being good enough,” you say in the 2019 documentary “Wonder Boy.” What do you fear today?

If there’s one thing that never changed, it’s that I’ve always felt like I had to push myself more than others.

I am part of the fashion ecosystem, now. I have a feeling of being recognised. Perhaps what I fear most is being forgotten.

Despite all this world of rhinestones and glitter, there is a deep loneliness, a deep quest to be loved.

You talk about wanting to celebrate Balmain’s heritage. How can you keep that memory alive without falling into nostalgia?

What I am trying to create at Balmain is a contemporary and living museum which does not necessarily consist of archiving, in the physical sense, but of multiplying connections, activations, beyond social networks.

You hold a festival by inviting 10,000 people [to your fashion show], you do a collaboration with Beyoncé for her Renaissance album (2023), creating with her 17 couture pieces. You do things remain in memories and in hearts. The trend leaves, the style stays. Balmain has its own style, that’s what will make Balmain stay.

Beyoncé is just one of the stars you’ve partnered with. What are links that unite you with your muses?

These are bonds of love. I will never allow myself to associate with people without having a deep admiration for them. I think of Kim [Kardashian], of Beyoncé. These are connections that come from the heart. I wouldn’t be the same person if I hadn’t dressed Kanye West 10 years ago. Putting Rihanna in the campaign in 2014, or Kim in 2015 wasn’t easy. At the time, people were wondering about her influence in fashion and luxury. When I chose Kendall Jenner and Gigi and Bella Hadid to walk for us, many doubted their legitimacy on the catwalk as they had come from social networks and reality TV. But I drew on their energy and their talent to build for the future.

Who will be next?

I’m not asking the question of who will be the new Kim, the new Claudia [Schiffer]: they are irreplaceable. But I wonder who this person will be who will captivate me like Kim captivated me. She could come from anywhere. This kind of beauty is about self-confidence. Beauty that allows a person to shine, to illuminate a room. It’s an assertive kind of beauty that does not correspond to any real canon.

Was growing up in a city considered by some as “provincial” a handicap in Paris fashion?

Bordeaux is an extraordinary city which has its strengths and weaknesses, its strong heritage, its architecture which ranges from Gothic to Napoleon, its vineyards. It is very anchored in France. As a child, I suffered from a city that was very conservative, with harsh clichés and prejudices, but I would not describe it as provincial.

I drew strength from it: if I understand the world of Balmain, it is because there is a very strict side that Bordeaux gave me in my way of being, of carrying myself, in my obsession with navy blue jackets with gold buttons. I wear my hair in braids, but I also always want sailor tops and tuxedos.

“I am in love with culture, with the idea that beauty transcends gender, borders, time.”

You’ve become massively famous on social media, with nearly 10 million followers on Instagram. How do you approach this tool?

Social media is as important as ever, but I have learned to move away to protect myself. At the beginning, there was a certain spontaneity and freedom. Now there is too much cyber-bullying. Whatever you do, you know there is going to be a huge community that will love you and a huge community that will hate you. I expose myself less.

Fashion has become more inclusive thanks to social media, which has called out collections, stylists, campaigns, silhouettes. But the danger today is that a lot of hatred is emerging.

A business driven by social media comments forces certain houses not to be themselves, or to take positions that are hypocritical — and they lose credibility. What is even more dangerous is to deny the past. To better understand the future, you need to have a vision of history. Criticise the past, yes, but don’t deny it. I am against cancel culture.

Let’s talk about the theft Balmain was the victim of last season. What happened?

A Saturday in late September at 2 p.m., my collection director told me that around fifty pieces for the Summer 2024 show had been stolen during an armed robbery, between Roissy [where Charles de Gaulle airport is located] and Paris. The driver was traumatised.

We had to figure out what to do: there were lots of suits missing, as well as denim, jersey, jewellery. We only managed to redo some of the pieces for the show. This experience taught me that as long as the pieces are not on the runway, there is still a risk. Nothing is guaranteed. Never think “we made it.”

The case is still ongoing.

We recently worked together when you created some pieces for Beymen’s “Golden Opulence” exhibition about Ottoman craftsmanship. You created a dress, a suit, two pairs of extraordinarily embroidered shoes. What was your inspiration for this project? [Laurence Benaim curated the exhibition; Beymen is owned by the same group as Balmain].

I am in love with culture, with the idea that beauty transcends gender, borders, time. For me it is not linked to any identity or ethnic assignment. The project combines the heritage of Monsieur Balmain in Parisian tailoring with Ottoman splendour. They are the summary of what I am: the mix of cultures, the beauty of the East and the West together. Nothing gives me more pride than making two cultures shine and bringing them together.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Credit: Source link