Photo: Douglas Elliman Real Estate, Corcoran Group, Serhant LLC

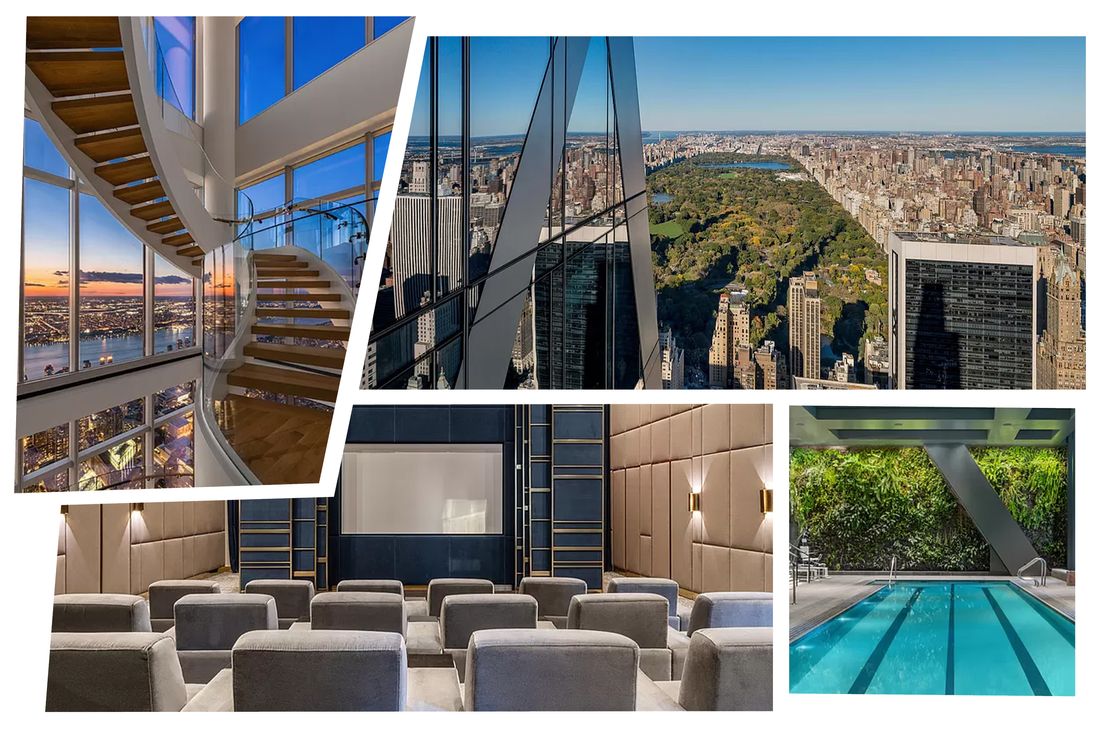

If you want views of Central Park and at least 6,000 never-before-lived-in square feet from which to admire them, you’ve got a lot ot choose from right now: Central Park Tower’s 17,545-square-foot penthouse — “a once-in-a-generation residence” — is on sale for 22 percent off its original asking price of $250 million. An 8,000-square-foot duplex at MoMA Tower, an asymmetrical crystalline skypiercer designed by Jean Nouvel, has been trying to get $63.18 million for the past five years. Over at 111 West 57th, $54.6 million will buy you a “spectacular, one-of-a-kind” duplex with “breathtaking, unobstructed 360-degree vistas.” (IMMEDIATE OCCUPANCY is plastered atop the building’s StreetEasy listings.)

An image of the “grand salon” with 27-foot ceilings at Central Park Tower, which was featured in the initial $250 million listing and the reduced $195 million one.

Photo: Serhant LLC

While the low-interest-rate-fueled buying spree of the past few years burned through most of New York City’s residential inventory, it barely touched Manhattan’s newly built trophy apartments. On Billionaire’s Row, 23 percent of sponsor units remain unsold, according to an analysis by appraisal firm Miller Samuel. And that’s not counting all the people looking to offload the ones they previously bought, which likely brings the total percentage of trophy apartments seeking buyers closer to 50 percent. “Many people thought the super-luxury market was wider and deeper than it actually was,” says Jonathan Miller of Miller Samuel. There just aren’t as many billionaires looking for real estate to park $30 or $40 million as developers thought there were.

Things started sunnily enough: The first few ultraluxurious skyscrapers — 15 Central Park West, One57 (at first, at least), and 432 Park (pre leaks, creaks, and elevator entrapments) — seemed to coast on some combination of FOMO among the megawealthy, bragging rights, and the promise of a sweet return upon flipping. But then more went up. And more. “For a while it was like, ‘Oooh, 18-foot ceilings,’” says one broker. “Now it’s like, ‘Oh, you also have 18-foot ceilings.’” Suddenly, an Extell Tower penthouse was not, as investor Bill Ackman once said, “the Mona Lisa of apartments,” but more like a mid-range Caravaggio. One57, in particular, where Ackman bought, developed a bad resale track record: One penthouse there traded at 30 percent less than the buyer had paid a few years earlier.

An image of the MoMA Tower’s penthouse, which has open city views and has been featured in the several listings since 2019.

Photo: Douglas Elliman Real Estate

Mostly, though, stuff just sat, gathering dust. At 111 West 57th Street, also known as Steinway Tower, which launched sales in 2019, less than half of the 60 units have sold, according to Miller Samuel. This summer, one of the project’s lenders, Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance, wrote off $82 million in debt tied to the project, citing sluggish sales, Bloomberg reported. “While there has been a modest pickup in foot traffic and buyer interest … the velocity of unit sales remains behind expectations,” the CEO told investors in an earnings call.

A photo of 100 E. 53rd St, Apt. 55A, shows the “stunning great room and kitchen and dining area with three sprawling exposures with luminous floor-to-ceiling windows.” This apartment just went on the market, but the building has been selling slowly.

Photo: Corcoran Group

Which has meant discounts on Billionaires’ Row (comparatively speaking). This fall, Gary Barnett dropped the price of the 17,500-foot penthouse at Central Park Tower to $195 million. Otherwise, the tower, which launched sales in 2020, is 59 percent sold, according to Miller Samuel’s analysis, with units selling at about a 25 percent discount. The Real Deal has reported that the building’s expected $4 billion sellout is now closer to $3 billion. But what, Barnett argued, was wrong with a little showmanship, if dealmaking followed? “The original pricing on these units were headline prices,” he wrote in a statement to The Real Deal after dropping the penthouse price. “We have recently sold a significant amount of inventory at the top of the building and now want to get serious about selling these two showcase homes.”

There were a lot of “headline prices,” as it turns out. Closings at MoMA Tower this year have averaged about a 20 percent discount, according to an analysis of sales data on StreetEasy. The building is now 61 percent sold. The more modestly priced Foster + Partners–designed luxury condo down the street, the Selene, is about 59 percent sold, according to Miller Samuel. At this rate, buildings in this rarefied market will average about a decade to sell out.

A photo of Steinway Tower’s pool, one of the building’s many amenities, which was featured in a recent listing. A slower-than-expected sellout led one of the project’s investors to write off some of the debt this summer.

Photo: Corcoran Group

Another issue is the lackluster appeal of many newly created luxury districts. Stephen Ross’s fantasies about the allure of the far (far) West Side have been collapsing, to all appearances: At 35 Hudson Yards, only 50 percent of the units have sold in four years, The Wall Street Journal reported this summer, with some of the larger units trading for discounts of more than 40 percent. Discounts were even steeper — up to half off — for active listings. (It’s worth noting that the exception to the ho-hum billionaires’ trophy market — 220 Central Park South, which seems to have snagged much of the available buyer pool for this kind of thing — is actually on Central Park.)

A photo of a living room at 35 Hudson Yards that showcases the development’s city views.

Photo: Corcoran Group

There’s very little urgency for buyers to buy anything right now, one broker told me, even for much more desirable real estate, like, say, a townhouse on the Upper East Side. Of course they’re not scrambling to snap up penthouses in Hudson Yards. “It was supposed to be the fashion, the media, the retail center of the world. It was going to be where Google and LVMH were headquartered. It’s very far from that vision,” he says. “Can we stop calling all these things trophies? It’s in the middle of nowhere.”

Credit: Source link