(Kitco News) – A recent publication from the World Bank includes one of the most concise and compelling explanations of central bank de-dollarization and gold purchases to date.

The Gold Investing Handbook for Asset Managers was authored by Kamol Alimukhamedov, Deputy Managing Director of the Central Bank of Uzbekistan and a Member of their Investment Committee. It provides a comprehensive overview of gold as an investment, including its market structure and strategic asset credentials, as well as its trading, custody, logistics, and accounting practices. Much of this will be familiar territory for precious metals people, though the inclusion of statistics and studies right up to 2023 makes it a valuable update for even seasoned gold investors.

Where the Handbook truly stands out is its clear-eyed and unflinching analysis of the growing trend among central banks to reduce their holdings of U.S. Treasuries while simultaneously increasing the percentage of their reserves allocated to gold.

“In the modern era, gold continues to play a critical role in the global financial system, serving as a hedge against inflation, a safe haven asset, and a reserve asset for central banks,” Alimukhamedov notes in the introduction. “The role of gold as a reserve asset for central banks has been a significant driver of demand for the precious metal.”

The author lists several economic and geopolitical challenges that have served to bolster gold’s position as a safe haven asset, and ends with the one that ignited the current push towards de-dollarization (all emphasis mine).

“The market disruptions brought about by the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the US and China trade war, Brexit, and the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as a prolonged period of negative real interest rates and geopolitical uncertainties caused by financial sanctions imposed on Russia to freeze its foreign reserves, reinforced the strategic importance of gold as a buffer against financial instability.”

He also noted the results of a 2022 World Gold Council (WGC) survey in which asset managers chose ‘historical position’ and ‘performance during times of crisis’ as their strongest reasons for holding gold.

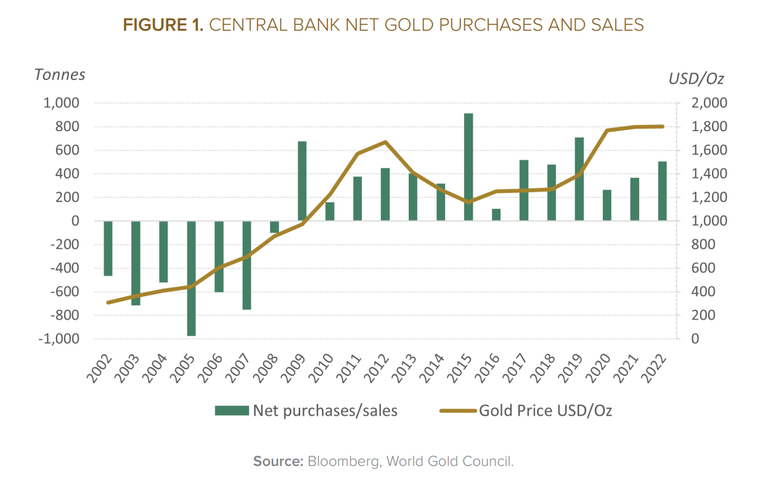

Alimukhamedov also points out that, beginning in 2022, the world’s central banks suddenly became far more interested in growing the proportion of their reserves devoted to gold.

“Central banks in 2022 were also more optimistic on gold as a reserve asset, with 61 percent of respondents stating that they expect global gold reserves to increase over the next 12 months,” he wrote. “Central banks’ stance against gold shifted in the period following the GFC, and they have been the net buyers since then, despite ever-increasing gold prices, after having been net sellers in preceding periods.”

Of course, Russia invaded Ukraine just two months into the year, with the United States and its allies levying the first wave of account freezes, asset seizures, and sanctions against Moscow in the weeks and months that followed.

The section of the Handbook devoted to geopolitical considerations goes into greater detail about how and why central banks are increasingly trading in their greenbacks for gold.

Alimukhamedov notes that research has established “a positive relationship between gold prices and geopolitical risk, even when financial market uncertainty is taken into consideration.” This research distinguishes between “expected or perceived geopolitical risk and actual or realized geopolitical risk, concluding that the latter is more important in driving gold prices.”

Other research indicates that “reserve managers consider gold to be a means of protecting against economic and geopolitical risks, and they therefore tend to increase their gold holdings during times of uncertainty or high geopolitical risk,” while reserve managers in emerging markets “tend to increase their gold holdings when there is a risk of financial sanctions.”

The author again underlines this point in the research cited. “The largest increases in gold holdings by central banks often occur when the banks anticipate or face financial sanctions,” he wrote. “The study’s econometric analysis revealed that both the volume and the value of gold reserves tend to rise in response to sanctions imposed by major economies such as the Euro Area, Japan, the United Kingdom, or the United States, in either the current or the immediately preceding years.”

He also provides detailed historical data supporting the assertion that in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the central banks that most fear Western sanctions are the ones driving sovereign gold purchases.

“Recent sanctions against Russia have raised the possibility that other countries’ central banks may shift their reserves from foreign exchange into gold,” Alimukhamedov writes. “This is because gold is a physical asset that can be stored domestically, unlike foreign exchange reserves, which can be frozen by sanctions. In half of the ten highest annual increases in gold stockpiles since 1999, the affected country was sanctioned during the previous year or two. Other cases revealed that the increases occurred in response to unforeseeable political events such as financial crises or coup attempts, which is consistent with previous findings.”

“Furthermore, gold purchases by ‘active diversifiers’ frequently coincided with political, economic, or financial shocks,” he added. “This lends credence to the notion that geopolitical events influence gold price movements and may be linked to fears about future penalties.”

Alimukhamedov thinks this shift towards gold could have significant implications for the global economy. “If more countries start to hold gold, it could boost the price of gold and make it more expensive for countries to use gold as a reserve asset,” he writes.

He then cites research that suggests this may end with the emergence of an entirely new financial paradigm.

“There is an argument that, in the aftermath of Russia’s supply-side crisis and the sanctions imposed on Russia, the world is transitioning from the Bretton Woods era, which was backed by gold bullion, to Bretton Woods II, which was backed by inside money (treasuries with unhedgeable confiscation risks), to Bretton Woods III, which was backed by outside money (gold bullion and other commodities),” he writes. “The belief is that the Russian sanctions create incentives for central banks to abandon the dollar in favor of gold and for governments to cash in their dollar reserves for stocks of other commodities.”

Alimukhamedov concludes the geopolitics section by noting that the sanctions against Russia “highlight the importance of gold as a reserve asset.

“It remains to be seen whether other countries will follow Russia’s lead and increase their gold holdings,” he writes.

Two years’ worth of data and analysis suggests they already are.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect those of Kitco Metals Inc. The author has made every effort to ensure accuracy of information provided; however, neither Kitco Metals Inc. nor the author can guarantee such accuracy. This article is strictly for informational purposes only. It is not a solicitation to make any exchange in commodities, securities or other financial instruments. Kitco Metals Inc. and the author of this article do not accept culpability for losses and/ or damages arising from the use of this publication.

Credit: Source link